DCIS FAQs

What are the symptoms of DCIS?

Are there different types of DCIS?

What is DCIS?

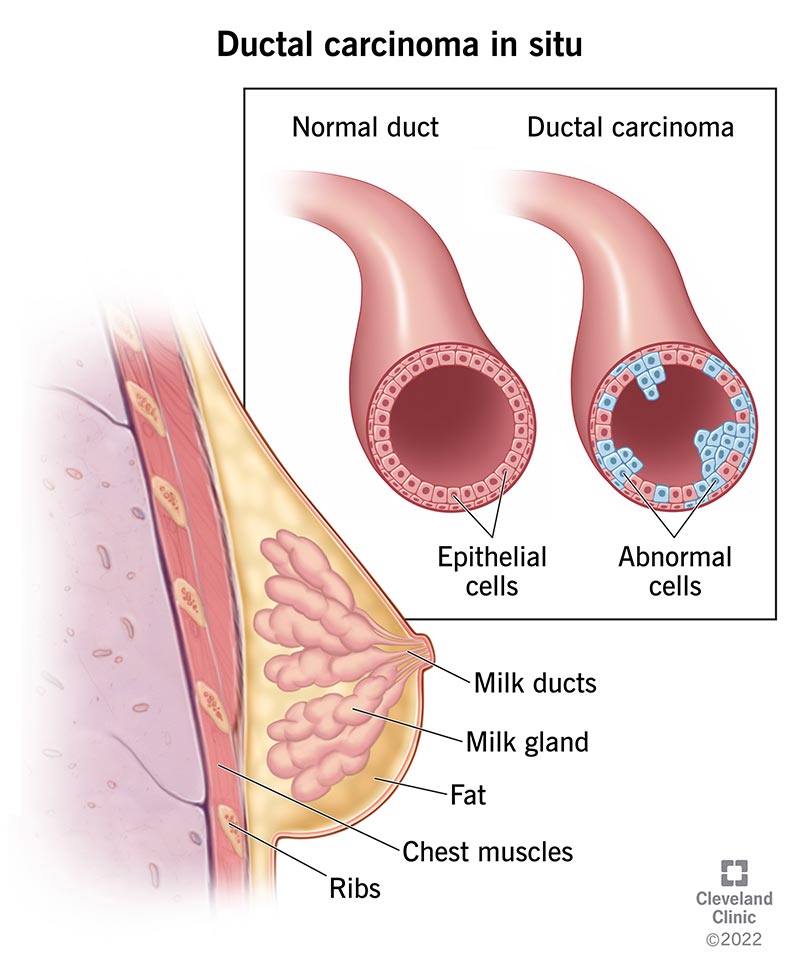

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) is a breast condition that is characterized by the presence of abnormal cells that are contained inside the milk ducts of the breast and have not spread to other parts of the breast or body. DCIS can, but often does not, lead to invasive breast cancer. DCIS is sometimes referred to as stage 0 cancer, pre-cancer or a risk factor for invasive cancer.

Is DCIS Cancer?

This is a very difficult question to answer in a short FAQ because there are leading experts on both sides of this debate. The short answer is that it depends on who you ask and how they define “cancer.” For more information, read our blog post on Should DCIS be Called Cancer?

When viewed under a microscope, the DCIS cells look like cancer cells; however, they do not necessarily behave the same way as invasive breast cancer. By definition, DCIS cells are “in place” and cannot invade or spread to other tissues in the body. DCIS cells have the potential to turn into invasive cells, which is why it is treated. The science is unsettled on the exact circumstances and mechanisms by which the change occurs.

What are the symptoms of DCIS?

Typically, there are no outward signs or symptoms of DCIS. A small number of patients may have a lump in the breast, fluid coming out of the nipple, or skin changes.

How is DCIS diagnosed?

Most DCIS diagnoses begin when a radiologist sees suspicious tiny white specks known as “microcalcifications” on a screening mammogram. The radiologist may recommend a diagnostic mammogram to take additional images at higher magnification from more angles. If the area of concern requires further evaluation, the next step is a breast biopsy (typically a core needle biopsy, or in some cases, a surgical biopsy) to remove a sample of breast tissue. The sample is then sent to a lab and examined under a microscope by a pathologist to determine whether abnormal cells are present, and if so, how aggressive those abnormal cells appear to be.

Are there different types of DCIS?

Yes, DCIS is highly variable based on a number of factors and is generally categorized as “low risk” or “high risk.” The main distinguishing features between different types of DCIS are the nuclear grade and hormone receptor status, both of which are determined by the pathologist who reviews the biopsy tissue sample.

- Nuclear grade: DCIS can be low, intermediate/medium or high grade. The grade is an indicator of the projected risk level that the DCIS will progress to invasive cancer. Low and intermediate/medium grades are considered low risk and high grade is considered high risk. Low risk DCIS is less likely to progress to invasive cancer than high risk, but low risk does not mean no risk. Regardless of grade and risk level, all DCIS is noninvasive and referred to “stage 0”.

- Hormone receptor status: DCIS can be hormone receptor-positive or hormone receptor-negative based on the presence or absence of certain proteins known as estrogen and progesterone receptors. If these receptors are present, it means that the hormones estrogen and progesterone can attach to them and stimulate the abnormal cells to grow. Knowing hormone receptor status of DCIS is important, because it helps determine whether hormone therapy might be an effective treatment option.1

Other distinguishing features of DCIS include the architectural pattern and the presence or absence of comedo necrosis. The architectural pattern is the visual image of the abnormal cells. Comedo necrosis is a collection of dead or dying tumor cells that can sometimes be found in the ducts and be an indicator that the tumor cells are growing quickly. This information is also contained in the pathology report.

These features, combined with other factors such as genetic history, age and lifestyle, contribute to a patient’s overall projected risk level.

Risk levels are a source of debate in the medical community, and there is heterogeneity among pathologists’ review of DCIS biopsy samples. Confidence in the pathology results is extremely important because it will inform the treatment plan. For this reason, it can sometimes be helpful to have the opinion of a second pathologist on the tissue sample.

How is DCIS treated?

In the same way that not all DCIS is created equal, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach for treatment. That said, the current standard of care in the U.S. is the same for all types of DCIS. Emerging research may lead to some changes in the conventional treatment of low risk DCIS, but at this time, alternative treatment plans are rarely available outside of a clinical trial.

Typically, DCIS is first treated with surgery – either a lumpectomy or a mastectomy. In a lumpectomy, the surgeon removes the area of DCIS and a margin of healthy tissue that surrounds it. In a mastectomy, the surgeon removes all the breast tissue. Mastectomy patients can decide whether they want breast reconstruction to restore the appearance of their breast, and this may be done at the same time as the mastectomy or in a later procedure.

Some lumpectomy patients will go on to receive radiation.

If the DCIS is hormone receptor (HR)-positive, five years of hormone or endocrine therapy is typically also recommended.

Some women with low risk DCIS may be able to undergo active monitoring, where in lieu of surgery, a patient has regular imaging and check-ups with her doctor to watch for any signs of worsening of the DCIS or invasive progression. Active monitoring can also be combined with hormone therapy to further reduce risk of invasive disease.

Each of these treatments carries different risks and side effects. What may be the right treatment for one patient may not be the right treatment for another. It is important for DCIS patients to work closely with a trusted doctor and evaluate all the available information about their DCIS and their individual risk profile when deciding on a treatment plan.

Please visit our treatment options page for more information.

Is DCIS life-threatening?

No. By definition, all DCIS is noninvasive and confined to the breast ducts.

Why is DCIS controversial?

DCIS is controversial is because there is a tremendous amount of uncertainty about its natural progression and what causes DCIS cells to turn invasive. While there are risk factors to consider, there is no surefire way to predict which DCIS will progress to invasive breast cancer and which will lie dormant for years or even decades, and never become life-threatening. This uncertainty has led to disagreement among some doctors as to the optimal treatment for DCIS, particularly for low risk DCIS. It has also led to highly variable practices among doctors in how they talk to their patients about DCIS, which in turn has created an environment of misinformation, confusion and fear.

Some of the most prevalent controversies include the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS, whether DCIS should be called “cancer”, and the use of active monitoring in managing low risk DCIS. More research is needed to shed light on these issues. In the meantime, all patients facing a DCIS diagnosis should have access to the contours of these debates and the relevant available data from all sides.

- American Cancer Society, Breast Cancer Hormone Receptor Status. ↩︎

Subscribe below for the latest DCIS news and updates.