When we talk about progress in breast cancer, we often point to the encouraging news that deaths from invasive breast cancer have steadily declined over recent decades—thanks to advances in detection, treatment and care.

But for DCIS, there is weak or even no evidence that our current treatments actually reduce the chance of dying from breast cancer. A new study published in Breast Cancer Research looked closely at this question, and the results raise important concerns.

Understanding trends in mortality after a DCIS diagnosis helps us see whether our current practices are having the intended effect, and can point to gaps in care or areas needing more research.

What Did the Researchers Do?

The team looked at U.S. cancer registry data (SEER) from 2000 through 2021, tracking women who were first diagnosed with DCIS and comparing them to women first diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Researchers wanted to see whether death rates after a DCIS diagnosis have gone down, stayed the same, or gone up over time. They also looked at differences by race and ethnicity to see whether death rates after DCIS vary among different groups.

What Did They Find?

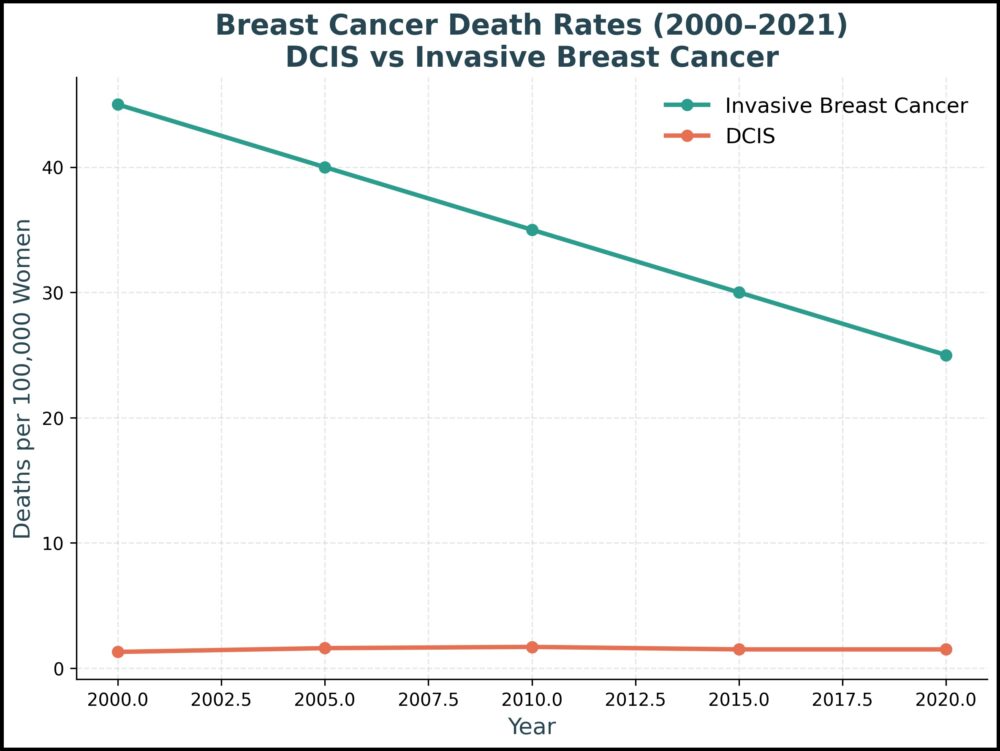

- Deaths after a DCIS diagnosis are rare—much less frequent than deaths after invasive breast cancer. Over two decades, about 2,175 breast cancer deaths occurred in women whose first diagnosis was DCIS, as compared to 61,000 deaths among women with invasive breast cancer.

- Unlike invasive breast cancer, DCIS death rates have not clearly declined. Death rates after invasive breast cancer dropped about 1.6% each year, thanks to better screening and treatment. For DCIS, however, there was no clear downward trend.

- Racial disparities are stark. In the years 2017–2021, black women with DCIS had an 87% higher death rate compared to white women. For invasive breast cancer, black women also had worse outcomes — with death rates about 39% higher than white women. These differences cannot simply be explained by diagnosis rates, suggesting that access to care, treatment differences, or underlying biology may play a role.

Why This Matters:

Despite decades of treating DCIS, we don’t have strong evidence that current approaches reduce the risk of dying from breast cancer. Most studies on DCIS focus on whether it comes back or progresses to invasive cancer — but rarely on whether treatment actually saves lives.

This new research is a call for more studies that look directly at breast cancer–specific mortality, and for tools that can better identify which DCIS cases are most dangerous.

The racial gaps in death rates are especially concerning. They point to deeper issues — including unequal access to care, treatment delays, and possible biologic differences — that require urgent attention.

What Are the Study Limitations?

Like all studies, this one has caveats:

- It relied on registry data and death certificates, which can sometimes misclassify the cause of death.

- It did not include every U.S. population, so results may not reflect every community.

- The follow-up period (using a 25-year lookback) may have missed some very late deaths.

Still, this is one of the most complete national pictures we have of long-term outcomes after a DCIS diagnosis.

What This Means for Patients

- DCIS is not one-size-fits-all. Some DCIS may never become life-threatening, while others may progress. We urgently need better tools to predict which cases are which.

- Shared decision-making is key. If you are diagnosed with DCIS, ask your doctor about your personal risk factors — such as age, tumor features, genetics, and overall health — and how they shape your treatment options.

- Equity matters. Advocating for access to high-quality care and participating in clinical trials (when available) are important steps toward closing outcome gaps.

- More research is needed. While outcomes for invasive breast cancer continue to improve, the same cannot be said for DCIS. Future studies and clinical trials should aim to see if new therapies or care approaches lower death from breast cancer after an initial DCIS diagnosis, not just whether DCIS recurs or invasive cancer develops.

To read the full study, click here.

Subscribe below for the latest DCIS news and updates.